How we could achieve equity

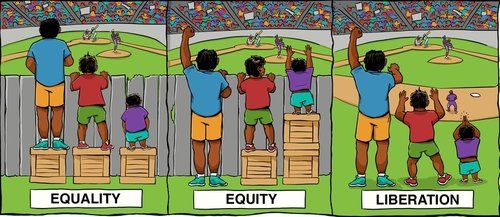

Equity is giving people what they need, whereas equality is giving everyone the same thing. We can only achieve equity by assessing disparities in opportunities, outcomes, and representation and redressing those disparities through targeted actions[1].

Image Credit: A collaboration between Center for Story-based Strategy & Interaction Institute for Social Change.

Equity means recognizing that we do not all start from the same place and therefore, have different needs to achieve the same outcome. Ignoring the many different barriers faced by people and giving everyone the same thing, is likely to maintain and can sometimes worsen disparities and exacerbate inequity.

We need to be aware that achieving equity can challenge and change the status quo. It means correcting power imbalances. This is likely to be resisted by those who have the power and benefit from the status quo.

steps to achieve equity

step 1 assess disparities and barriers and their causes and context

The first step is to identify and name marginalisation and discrimination (even when this can be obvious and well-known).

Data is a good place to start in analysing disparities. However, aggregated data can hide variations by characteristics such as race and ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, income levels, and geography. For example, the Australian Year 12 completion rate of 81.7% hides the facts that there are differences between male and female students (74.6% for males and 83.2% for females) and between major cities and remote/very remote areas (81.7% in major cities compared to 65.3% in remote/very remote). Therefore, we often need to disaggregate data to better understand the origins and nature of existing inequities.

In addition to data, we need to recognise that marginalized populations within any community have experiences that are very different from those of many individuals and organizations who work to help them. As outsiders, we often don’t know enough to be as helpful or effective as we should be, so we need first to talk, listen, and learn. A complete assessment of the factors causing inequity requires a holistic understanding of the life experience of marginalized populations that can come only from interviews, surveys, focus groups, personal stories, and authentic engagement.

Too often data sets, particularly data sets that are solely quantitative, fail to capture the context that only the people most impacted and those closest to them understand. Frequently the analysis of the data is carried out by people who don’t have a lived experience of the subject matter.

recommendation: People with lived experience should be involved in designing the approach to collection of data and then actively engaged in the analysis, interpretation, and communication of the results. In some circumstances, including data as it relates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, data sovereignty – the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over this data – should be held by the people with the lived experience.

step 2 gain understanding of the system

Before working out how to redress the barriers and disparities identified in the first step, it can be useful to develop some understanding of the system that needs change. This can mean mapping out the various actors and interrelationships within a given system, potentially using a Theory of Change which can explore the process of change by outlining causal linkages in an initiative, (i.e., its shorter-term, intermediate, and longer-term outcomes) or a System Mapping or combination approach. However, we should avoid getting bogged down in the complexity of a system as you will invariably “learn as you go”.

This step should also analyse the power imbalances in the issue being considered, potentially using the four categories of power detailed below as a starting point.

Power can exist[2]:

- In resources

- Money

- Influence

- Knowledge

- In structures

- Decision making

- Agenda setting

- Roles – the ability to reward or coerce

- Legislation, rules, procedures

- Norm making

- In Identity and Relationships

- Who we know and how those bonds are reinforced

- How we show up and are recognised

- E.g., Our identities might be privileged, marginalised or oppressed

- In Framing

- The stories we tell about why things are the way they are

- The ability to shape/influence narratives

- The normalisation of status quo systems so, for example, we think that poverty is normal, and our current economic systems are the only way things could possibly be or what we should value and how we should measure our successes

Therefore, some examples of the questions that could be asked in this stage include:

- who benefits from the status quo and will likely resist change?

- what structures (e.g. policies, practices and resource flows) support the status quo?

- who currently has the power to make decisions?

- what are the relationships between those with the power to effect change?

- who are the recognised “experts” in this area?

- who has the power to influence decision makers?

- who has the power and desire to change the status quo?

- what is the narrative that supports the status quo and who controls this narrative?

- what assets are there in the affected communities that can be leveraged for change?

recommendation: It is important to work with community, recognizing and building on the people and power that make up the community. This approach requires that we see communities and people as assets, rather than as problems to be solved. We must actively recognise the talent and commitment of people, the importance of local relationships, and the value of institutions run by community members as the building blocks of change.

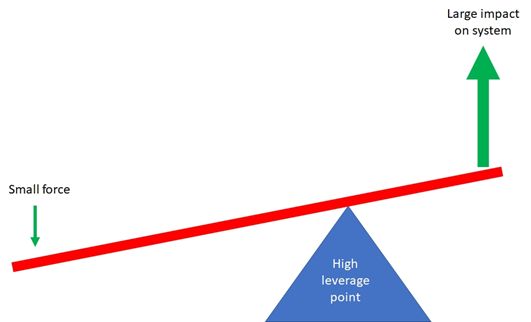

Once you think that you have some understanding of the system you can start forming a hypothesis about the best places to intervene (leverage points) in order to shift the conditions that hold a problem in place[3].

You might consider designing the solution for the person who is least well-served by the system you are trying to fix or design a solution that is inclusive of the needs of both the dominant and marginal groups but pays particular attention to the situation of the marginal group. Chances are, if you get it right for those who have suffered the most, others will benefit too. That’s the power of equity.

step 3 Implement interventions to meet people’s needs now

The inequity of wicked problems can rarely be solved by implementing one program at a time. Equity will need to address the root causes of social problems at a community, regional or national level but this systems change will typically take some time. Therefore, we firstly need to identify and implement interventions that improve programs and services that meet the needs of people who are struggling today.

Providing shorter-term programs and services can also inform the structural, systems and policy changes needed to achieve larger outcomes especially if they engage the community and get them involved in co-designing the systems change required for sustainable improvements in equity.

recommendation: Meet peoples’ immediate needs now while working on systems change for long-term, sustainable change.

step 4 Develop the strategy for systems change

To change a system to make it more equitable, we need to consider three types of changes[4]:

- Structural changes – in policies, practices and resource flows

- Relational and power changes – in relationships and connections, and power dynamics among people or organisations

- Transformative changes – the mental models, worldviews and narratives behind our understanding of social problems which are frequently used by those with power—intentionally or not—to conceal structural inequities

Working together in collaborations

Systems change normally is beyond a single organisation so the first step in developing a systems change strategy is determining who should be involved in a collaboration to effect change.

Within these collaborations it is important to work towards shifting power to the affected. For example, it is not enough to increase diversity in the decision-making process without changing the underlying dynamics of decisions made at the table by shifting culture and power. Those with formal power—in much of the Western world, mostly white and male—need to engage with, listen to, share power with, and act on the wisdom of the community.

This can involve ensuring that people with lived experience are part of the decision-making process, have the last say before any decision is made, have their capacity built to better participate in strategic discussions and have leadership opportunities created for them. It is important to “do it together” and distribute leadership and share power. This is unlikely to happen without specific strategies in the collaboration to share power.

Leverage point interventions

A systems change strategy needs to prioritise the high leverage point interventions where a small change can create a big impact and these can be any of the change types listed above.

Leverage points are like acupuncture points — places where a finely tuned, strategic intervention is capable of creating lasting change, creating positive ripple effects that spread far and wide. Leverage points also represent opportunities where participants can have greater impact by working together than they can by working alone[5].

When developing a strategy, we need to be aware that the approach to any particular systems change initiative very much depends on the type of system involved, and on the position of the change-agents within it: the specific situation will dictate the approach and one size will not fit all.

Some people and organisations focus on making structural changes but ignoring relationships, power dynamics and mental models can lead to irrelevant, ineffective, unaccountable, and unsustainable solutions. The tendency particularly holds if the solutions were developed in a context where marginalised groups had no voice and power. The slowness in Closing the Gap is a classic example of acting without giving First Nations peoples a voice and power.

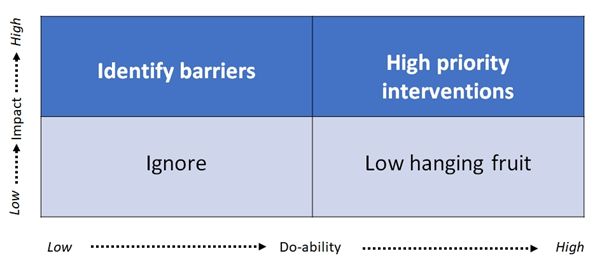

recommendation: In your collaboration, identify a number of leverage points which have clear positive outcomes and potential for scale and then assess your assets (right timing, power bases, available capacity, and potential for acquiring necessary resources) to determine the “do-ability” of each leverage point.

The goal is not to seek perfection but to give you a reasonable place to start so you can test, learn, refine and improve as you go. You should focus wherever possible on those interventions which have high impact and high do-ability. Sometimes, you may choose low hanging fruit which have high do-ability even if their impact is not that great as a means of building momentum.

step 5 Intervene, watch, adapt and learn

Now is the time to implement the high leverage point interventions where there is a realistic prospect of changing the system and observe what occurs. This is when your hypothesis developed earlier is put to the test. Look out for the reaction from those in power who are benefiting from the status quo and be prepared to deal with their response.

recommendation: Systems change is frequently messy with the relationship between an intervention and an outcome not always predictable, and you will need to build the evidence base for what works and what doesn’t and then learn as you go. This means embracing complexity and adapting the interventions based on your learnings.

conclusion

Within the social sector we are often painfully aware of systems failure, as evidenced by the growing need in so many areas and the very visible effects on the lives of vulnerable and needy people. Therefore, we need new ways of thinking about the social landscape and the players within it to achieve equity. For lasting change, we need to challenge conventional solutions and disrupt the powers that underpin the structures and supporting mechanisms which make the system operate in the current inequitable ways.

Charities, funders, corporates and governments working together can make an equitable society which will benefit us all, but we will need to be brave and in it for the long haul.

References:

[1] https://ssir.org/articles/entry/centering_equity_in_collective_impact

[2] https://www.arabellaadvisors.com/blog/questioning-four-types-of-power/

[3] https://www.aracy.org.au/documents/item/659

[4] https://hub.youthpowercoalition.org/t/the-six-conditions-of-systems-change/280

[5] https://medium.com/converge-perspectives/identifying-leverage-points-in-a-system-3b917f70ab13